A look at Anglo-Saxon England before the Normans

31 Jan 2026

This blog is based on a talk I gave to Mersham Historical Society. I approach Anglo-Saxon England through the ‘three orders of the world’ – those who work, those who pray, and those who fight.

It’s a notion that would have been readily understood at the time, and though Abbot Ælfric of Eynsham wasn’t the first to describe the orders, as he lived into the 11th century when my Book and the Knife novels are set, his explanation is useful (and straightforward).

Know, however, that in this world three orders are established.

Laboratores are those that labour for our sustenance.

Oratores are those who intercede for us with God.

Bellatores are those who protect our towns and defend our soil against the invading army.

Now the farmer labours for our food and the warrior must fight against our enemies and the servant of God must continually pray for us and fight spiritually against the unseen foes.

I discuss the implications of these aspects of England for 1066 – for William’s claim, the Norman invasion, and the bloody aftermath. What emerges I think is a nation of strengths… and weaknesses, but recognisably English, even then.

Those who fight – kings, earls and housecarls

The push back against the Danes begun by Alfred the Great in the 800s starts to create a recognizable England out of the old Saxon kingdoms by the 10th century. Northumbria, Mercia, Wessex, East Anglia, Essex, Kent and Sussex, who fight each other for supremacy – and sometimes ally with each other through marriage – will become earldoms united under a single king in the 11th century, but it’s not a simple process. People think of themselves as Mercians or Northumbrians before people of an ‘Engla-lond’. King Athelstan, arguably as successful as his grandfather Alfred in creating a nation state, has coins minted calling himself ‘King of the Britons’. No, you aren’t, say the Northumbrians and East Anglians, and rub the inscription off the coins they're sent.

Anglo-Saxon kingdoms (source: Wikipedia)

When we reach the reign of Edward ‘the Confessor’, earldoms have replaced kingdoms, with powers in raising taxes, administering laws and to levy armies for the king. These are indeed the men who fight. King and earls have professional trained soldiers at their service called ‘housecarls’, whose fighting gear is remarkably like that of Normans, with knee-length mail tunics, kite-shaped shields, and pointed helmets with noseguards. It’s the two-handed war axe that they have in common with the Danes that gives the housecarls away as Anglo-Saxon warriors. The earls can also call on a local militia called the ‘fyrd’ to fight when needed, a kind of Anglo-Saxon Dad’s Army, but though some have spears and shields, these are villagers and many only have makeshift weapons like pitchforks.

A housecarl (source: Regia Anglorum)

The Witan, a king’s council of earls, thegns and bishops who advise on church and state matters plays an important role in pre-Norman England, though it’s vital not to exaggerate this. The king appoints the Witan and listens to it – but doesn’t have to do what it says. Even so, as an assembly of England’s powerful men, it creates something of a balance between the King and his subjects, and the Witan does have to approve a new king, although the assumption is always that this will be an Ætheling, one of the immediate royal family. The Witan that approves Edward from the House of Wessex includes Earl Godwin, who rises to power under Cnut and has a hand in putting two of the Danish king’s sons on the throne before Edward finally gets a look in.

When Edward marries the earl’s daughter Edith, it brings the Godwins closer to royal power, and with the expectation that in the next generation one with their blood will sit on England’s throne. But Edward’s relationship with the Godwins is always fraught. When the Wessex try to regain the throne in 1036, Edward blames the earl for his brother Alfred’s death. A showdown in 1051 between Edward and the Godwins after he has become king leads to the exile of the earl and his family, but a year later he is back in force and Edward has to reinstate him. At this point the Norman Jumièges, Edward’s appointment as archbishop of Canterbury, flees to Normandy taking two Godwin hostages with him. William keeps them as collateral against Edward reneging on his promise to him of England's crown.

So who are the fighters in Thegn of Berewic, Part One of my novel series? Sighere thegn of Berewic is a Godwin, who Earl Godwin calls on to help repel the Wessex attempt to regain the throne. The earl’s son Harold Godwinson comes to Berewic with him and urges the thegn’s daughter Æadgytha never to forget her heritage as a Godwin. Later as a young woman, it is Æadgytha who will urge Harold to pursue the family’s cause and get the hostages back.

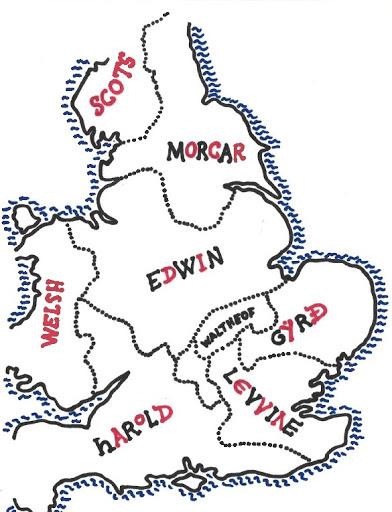

By 1066 the house of Godwin is the most important in England after Edward’s royal house of Wessex. The Godwins have been extending their grip on England’s earldoms through the 1050s, with Harold Godwinson following his father as earl of Wessex, Gyrth Godwinson becoming earl of East Anglia, and Leofwine Godwinson becoming earl of several smaller shires.

Tostig Godwinson becomes earl of Northumbria – so how come when we look at the map, Morcar, not Tostig, is earl of Northumbria in 1066? Tostig is put into Northumbria after the head of its ruling family dies, but he is a heavy-handed ruler who also taxes the locals harshly. In 1065 the Northumbrians revolt, and Edward – who with Edith is a Tostig supporter – orders Harold to put the uprising down. But Harold quickly realises the risk of a civil war and meets the rebels, after which Morcar, brother of Edwin earl of Mercia, is installed as new earl. Tostig goes into exile – but he’ll be back…

English earldoms in 1066 (source: Wikipedia)

It's important to remember at this point that the north and east of England is heavily settled by Danes. This area – the Danelaw – retains distinctive laws and customs. The Anglo-Saxons are horrified that Danes are in the habit of bathing once a week – excessive cleanliness!

Approximate boundary of the Danelaw (source: Wikipedia)

What’s significant when we look ahead to 1066?

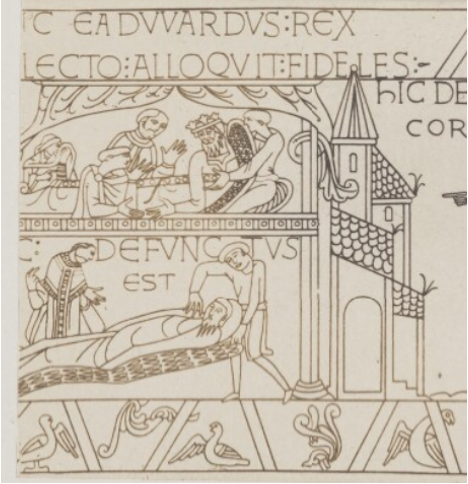

· Edward depends on the Godwins as kingmakers and the power in the land. He dies childless and as the Witan is in London for the dedication of his West Minster, they can quickly approve Harold as next king.

· The Danelaw keeps its distinctiveness. Major uprisings will happen in the north and east of England after 1066, but the old regional divisions mean there is never an England-wide uprising.

· Deposing Tostig in Northumbria makes a split between Harold and Edward/Edith and an enemy of Tostig that will prove fatal when he allies with Harold Hardrada of Norway and they invade. It also makes Mercians supreme in the midlands and north, though when Harold marries Edwin and Morcar’s sister Ealdgyth, Godwins and Godwin allies are firmly in control again.

King Edward on his deathbed, in the Bayeux Tapestry (source: Wikipedia)

Those who pray – (arch)bishops, priests and monks

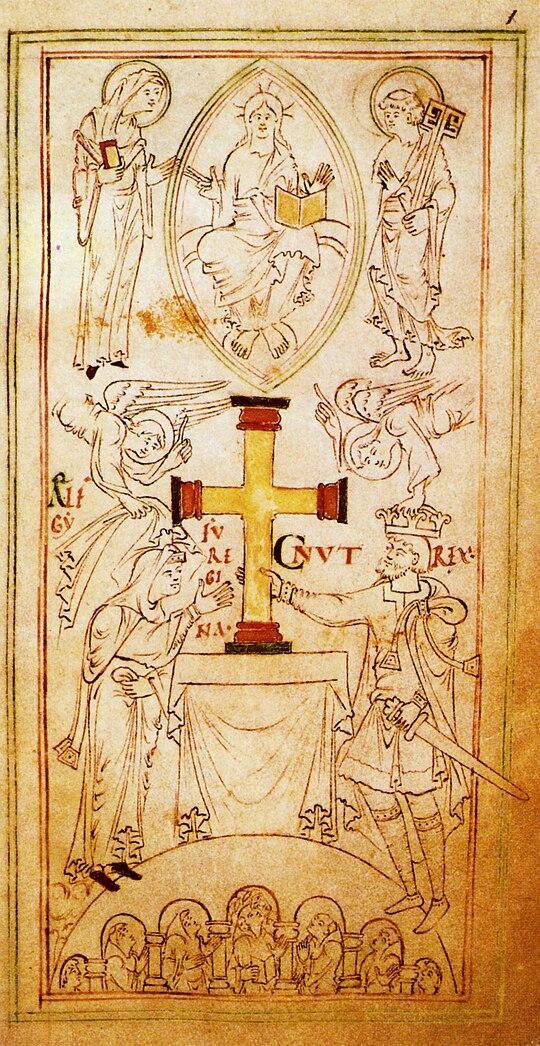

The church is long established in England by the 11th century. It has sent scholars like Alcuin to Europe and clerics like Bede are famous for their works on theology and history. It is wealthy and powerful and a major landowner; bishops control large areas and have places on the Witan. Kings and nobles gift wealth to the church such as the gold cross Cnut and his queen Emma give to Winchester.

Cnut and Emma gifting a gold cross to Winchester (source: Wikipedia)

England has some remarkable religious buildings. Built to honour a vow to the pope, Westminster Abbey is the creation of Edward, though he dies just before its consecration at the end of December 1065. He calls it his ‘West Minster’ of Saint Peter to distinguish it from his ‘East Minster’ of Saint Paul’s.

A reconstruction of the Anglo-Saxon West Minster (source: Wikipedia)

Who prays in Thegn of Berewic? Felip, of course, the Benedictine monk who in my novel, comes to England looking for the book of The Book and the Knife. Edward takes him on to help with building Westminster, as he has experience with building Cerisy for William of Normandy.

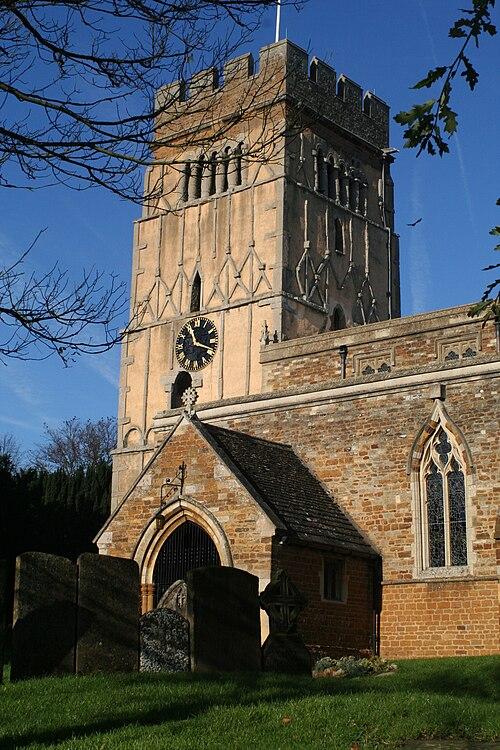

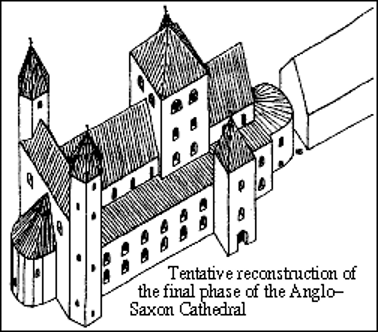

Canterbury is not far behind Westminster, and a great cathedral church. We have a good idea of the layout of the Anglo-Saxon cathedral from excavations that took place under the nave in 1993. A similar style to Westminster can be seen in its towers and roofs. But we don’t see these buildings if we’re looking at present-day Westminster or Canterbury, although some 50 Anglo-Saxon church buildings survive. The church in my fictional village of Berewic has been built by thegn Sighere, and with its short, squat tower is the only stone building in the village.

The Anglo-Saxon church of East Barton, Northamptonshire (source: Wikipedia)

The English church institution is one of contrasts. England has numerous saints like Ælfheah and Dunstan at Canterbury, whose relics are worshipped. Yet village priests are often uneducated and married (against reforms taking place in the wider church). Marriages of other villagers might be blessed by a priest, but it is a secular ceremony and a contract only between those involved. Church appointments are often contested between the Godwins and Edward. Archbishop of Canterbury Stigand holds on to the see of Winchester after his appointment, the sin of pluralism for which he is excommunicated.

A reconstruction of the Anglo-Saxon Canterbury Cathedral (source: Wikipedia)

The significance for 1066?

· The ousting by the Godwins of the Norman archbishop of Canterbury Jumièges for Stigand is another blow to Edward’s standing. Reform of the English church becomes a ‘war aim’ of William, and support from the Pope is based as much on this as for his claim to the throne. Stigand is deposed in 1070 by William who appoints Lanfranc, a Lombard who served him in Normandy, as his successor.

· By 1129, all fifteen Saxon cathedrals will have burnt down or been demolished, including Canterbury which burns down in 1067. A young monk there called Eadmer is a witness who will write about it and go on to record the lives of Lanfranc and the next archbishop of Canterbury, Anselm. Only two Anglo-Saxon bishops remain, and English saints are purged. William institutes church reforms such as the celibacy of priests.

· Abbeys such as Ely are often the centre of resistance to Norman rule, but their wealth makes them a target for attack, not only for supporting rebels and outlaws, but for acting as a ‘bank’ for dispossessed English nobles where they think their wealth will be safe. But William grabs the money to pay his followers for their help in putting down rebellions. Which leads to more rebellions, needing to be put down, so needing more money to be found…

Those who work – from thegn to slave

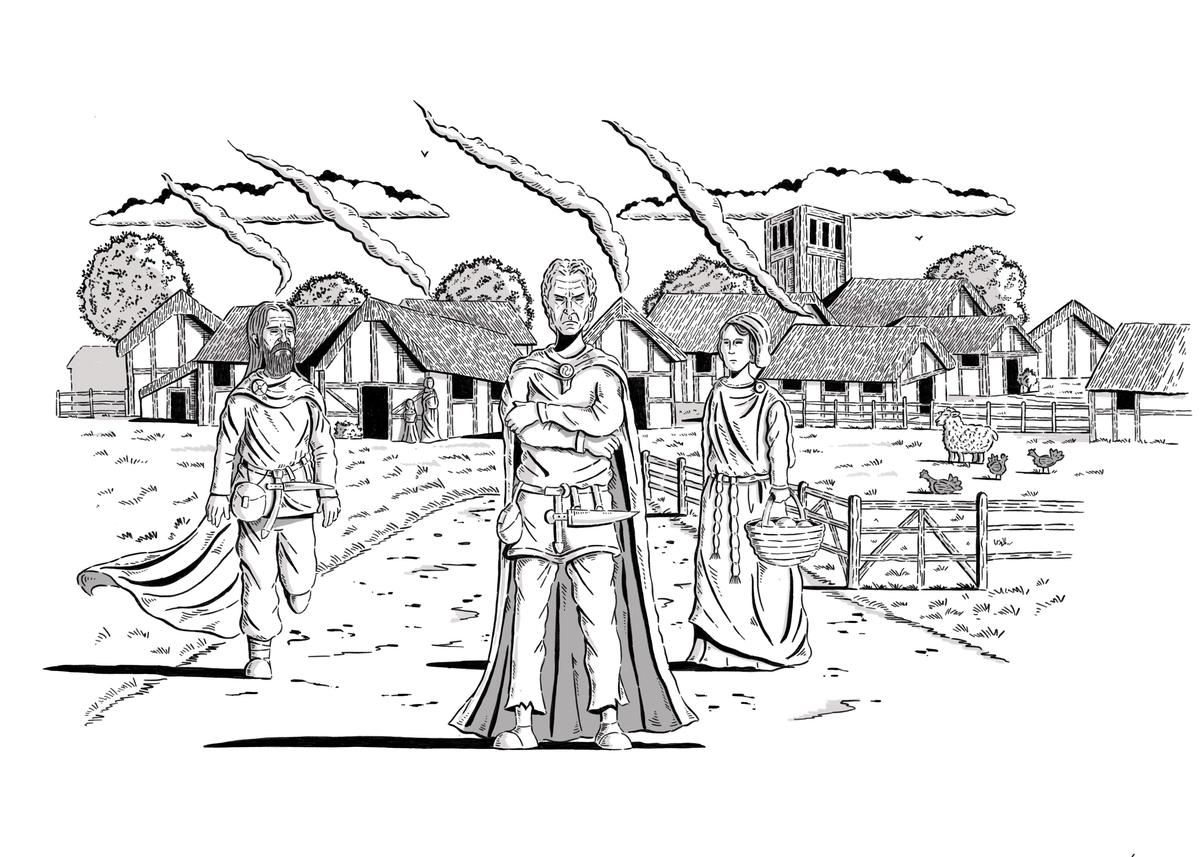

11th century England is a well organised and highly stratified society. Of a population of 2-2.5 million, only 10% of people are living in towns, although with their markets, craft workers and mints these are developing rapidly. Ruled over by its thegn, the village manorial estate, corresponding roughly in size to a modern rural parish, is the mainstay of the English economy and less the refuge now of the leader of a war band, more the seat of a country squire. A thegn holds his lands from the king and does duties for him such as military service, and overseeing fortification and bridge building work. Ranking between a hereditary noble and an ordinary freeman, this makes the thegn something of an anomaly in my three orders. On the one hand, he may be called on to fight for his king and he gives protection to his villagers in return for the duties they perform for him. On the other hand, he ‘works’ to ensure everything in his manor runs smoothly, balancing his own rights with the needs of villagers, and stepping in at times of crisis such as famine. In this system villagers may play their part as intermediaries, such as the reeve, who oversees the daily business of the manor, and mediates between the thegn and his fellow villagers. In Thegn of Berewic, Cuthred the reeve is an ambitious man who will clash with Eadric, adding to his sense of injustice.

The village of Berewic (illustration from Thegn of Berewic)

Ceorls are the freemen, farmers and independent landed householders of the village – the 'folcfry' (folk-free), that is, free in the eyes of their community. Ceorls are allowed to bear arms and considered worthy to serve in the fyrd and take part in folk meetings. Ceorls fall into three classes depending on the degree of rent paid to or duties performed for their lord (thegn) – from the geneat who is fully free to the gebur, who is a slave in all but name. In Thegn of Berewic Eadric is made a gebur who is allocated land in return for a long list of duties to his thegn, such as feeding his hound.

The villagers are essentially a labour force for food production, but there is some social mobility. Talking to the young Æadgytha, Cuthred tells her how a ceorl might gain status;

If his landholding rises to five hides, with church and kitchen, bell-house and burh-gate, he can even rank as a thegn, if he performs royal duties. And if he keeps his rank for three generations, it will pass to his heirs, even if his landholding later falls below five hides. Think on that!’

An Anglo-Saxon village family (source: Wikipedia)

Below still lower ranks in the village such as bordars and cottars, comes the lowest in Anglo-Saxon society; the slave. Slaves can be bought, sold or given away. Slaves are born of other slaves. Slaves can be captured in war, or become slaves as a punishment or because they can’t pay legal fines. In hard times the poor might sell themselves into slavery to avoid starvation. Slaves can buy their freedom if they earn enough, and sometimes they are freed in their owners’ wills.

The English administrative structure goes: earldom – shire – hundred – tithing. A tithing is equivalent to ten hides, a hide nominally being 120 acres, although by the end of the Anglo-Saxon period it is a measure of the taxable worth of an area of land rather than of any fixed area. A tithing comprises about ten households with a collective responsibility for law keeping – if one breaks the law, the rest bring the offender to justice or all are punished. Every tithing has to supply two men for the fyrd plus their equipment. If they’re needed, these men have to fight for 40 days, then they can go back to their land.

The plough and oxen team is the mainstay of food production, in a rotational system of winter and spring crops and fallow. A plough might only cover half an acre in a day, if there’s a problem with it, or the animals drawing it, or the soil is waterlogged, or frozen.

Me at the working end of a Kentish plough (in Brook Museum)

Famine is a constant threat if not enough food can be produced for the winter and into the next year. ‘And in this [year] was a great famine over the land of the English, and corn as dear as anyone remembered’ (Peterborough MS (e) 1043 [1044]). In the ‘hungry gap’ just before the harvest people may resort to grinding up anything for flour, including rye carrying a fungus called ergot that can lead to hallucinations when consumed.

Anglo-Saxon people also have rights to common land or waste for grazing hunting, fishing, foraging and gathering wood and turf. Anglo-Saxon kings have hunting grounds, but William and his successors will expand the royal forest area hugely to around 30 per cent of the country, into a reserve where no weapons, dogs, farming or building is allowed. There are severe penalties for infringement from fines to death.

Yet England is a wealthy country by the standards of north-west Europe. It produces fine metalwork, wool and cloth and exports them through its growing number of ports. Its abbeys and monasteries have vast treasures, and are producing fine illuminated manuscripts. And England has a highly efficient tax system – that came into place because it levied money to pay off the Danes (the ‘danegeld’)!

What bearing does all this have for 1066?

· England’s size, wealth and productivity make it attractive to the Normans. England is also seen as a soft target after 50 years of peace.

· The fyrd system twice hinders England’s military response in 1066, once when the men go home after William doesn’t show up over the summer, and in the eventual battle when the fyrdmen in the shield wall think the Normans are in retreat and go after them, only to be cut down.

· William rewards his nobles/mercenaries with land and confiscated estates. The English tax system allows William to raise money after the invasion to pay his followers, and the Domesday Book isn’t just a who’s who – it’s an ownership record that allows a full tax to be levied.

· The Normans are morally opposed to slavery – though slaves are recorded in the Domesday Book, it will die out in England.

· William retains the English administrative system, but he centralises it, with himself at the apex of a landholding system where a small proportion almost entirely of Normans hold nearly all the land.

· William’s forest laws remove commoners’ rights, but the Andredswald remains densely wooded and in The Book and the Knife novels is a home to outlaws fighting on against the Norman occupation.

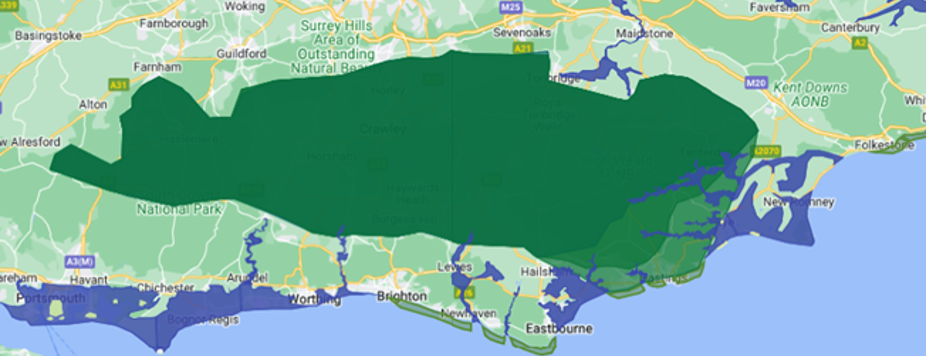

Location of the Andredswald in southeast England (source: Wikipedia)

In Thegn of Berewic, one of my characters sums Anglo-Saxon England up for Felip when he arrives. Osbern is a historical figure, Edward’s chaplain and cousin who lives at Bosham in Sussex, in the heart of the Godwins’ lands.

‘England is full of… contradictions, Felip. It upholds men’s freedoms, and relies on slavery for its meanest tasks. Its people are surly and quick to anger, yet they bear enormous hardship with calm and humour. It is on the edge of the world, yet the knowledge of the world comes to it. Its cathedrals and monasteries are ramshackle, and within them the greatest books are being written and copied. Contradictory, irritating, and ramshackle; yet there is much to love about England.’